David B. Stewart

Specially Appointed Professor

Tokyo Tech

Kazuo Shinohara (1925-2006) at age forty-six made his first journey outside Japan starting with Morocco and southern Europe and traveling for eight weeks. In the same decade, after submitting the plans for House in Uehara toward the end of 1975 he visited West Africa alone. Then, in 1979 he flew to Paris on the occasion of his first major dedicated one-man show there. And in 1982 he lectured in Sydney and Melbourne. In 1984 Shinohara was named first “Eero Saarinen Visiting Professor” at Yale University, from where he took the opportunity for a first-time visit to New York City. At the start of the next year, he traveled from the US East Coast to São Paulo followed by a visit to the Inca ruins in Peru, these last foreign trips coinciding with his sixtieth birthyear.

However, Professor Shinohara’s small atelier never received the opportunity to build abroad despite having participated in a number of competitions beginning with that for the DOM Headquarters in Cologne (1980), the exhibition project “Paris: Architecture and Utopia” (1989), the limited competition for the Agadir Convention Center in Morocco (1990), the invited Euralille Hotel-Office Project (1990-92, unfortunately canceled due to external reasons), and reaching a close with award of Second Prize in the Helsinki Contemporary Art Museum limited competition (1993).

Now that has changed!

The reason is that Shinohara’s early sixth work, Karakasa no ie [Umbrella House] of 1961 stood as of last year at this time in danger of demolition. The family of the original owner wished to move and, therefore, needed to sell the house. An application was made to Heritage Houses Trust (https:// hhtrust.jp/), a non-for-profit organization who specialize in finding new owners for homes of historical architectural value in Japan whose survival is for whatever reason compromised. Several “open house” events were held and eventually contact was established by the architect Kazuyo Sejima on behalf of HHT with the Vitra Design Museum (https://www.vitra.com/en-gb/about-vitra/campus/vitra-design-museum), who have now agreed to add Umbrella House to its public campus in Weil am Rhein in Germany, a suburb of Basel, Switzerland.

This great good fortune has during the time of coronavirus entailed numerous difficulties mitigated by the assistance of the architectural firm DEHLI GROLIMUND in Zurich, working together for over a year with two tireless TiTech doctoral candidates: Masaru Otsuka of Okuyama Lab and Naoto Kizu of Yamazaki Lab supervised by their professors.

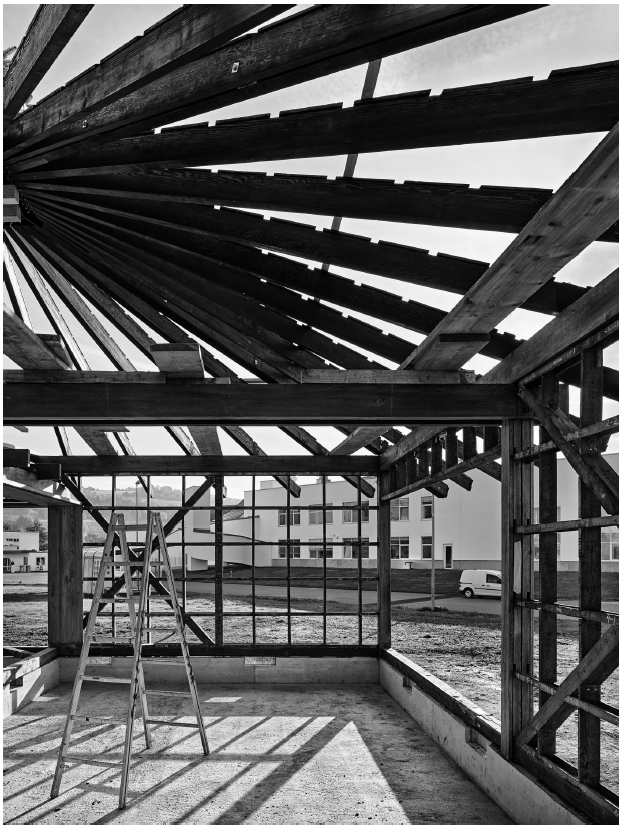

Happily, on October 15th 2021 a Richtfest [Topping Out (or Topping Off)] ceremony was able to be held at Vitra, led by the local German carpenters who had worked on re-erecting the framework of the house and repositioning the rafters, after the long journey by container from Japan of the set of original framing members.

For this a small ornamented evergreen tree is attached to the topmost point of the roof. The purpose is like a building site dedication in Japan to ensure or give thanks for the safety of all workers and thus provide an auspicious future for both the building and its occupants. There are in this way religious overtones, though not as in Japan any overt religious participation by members of the priesthood. A toast is proposed by the chief carpenter, with glasses raised four times before being thrown to the floor and smashed for good luck.

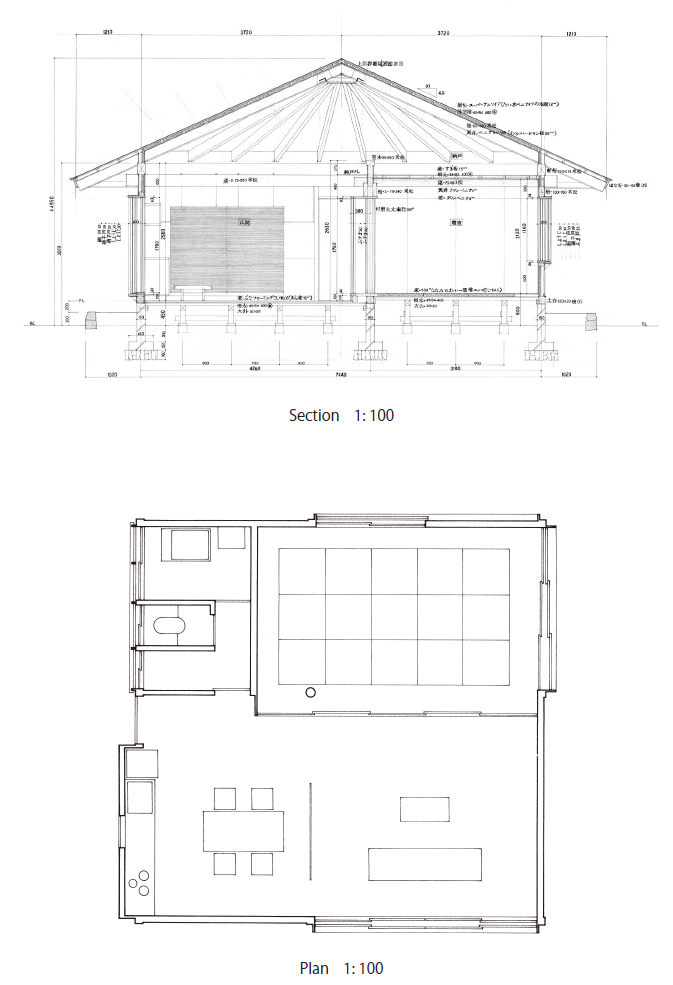

As for the house itself of 1961, which over the years few had visited, since Professor Shinohara was till the very end keen to protect the privacy of his clients, it is exquisite in its design as a single roughly 7.5m square interior with the rafter overhang extending very nearly to a full 10m. The earliest First Style houses are a good deal colored by their times, especially in the case of Shinohara’s very first work, House in Kugayama (1954), influenced directly by Tange’s majestic contemporary residence in Seijo (now both demolished) albeit at a much-reduced scale. A more general source of inspiration is the Maekawa-Raymond tradition, whose own houses located in Meguro and Shibuya respectively stand a decade apart, dating to 1941 and to 1953. More specifically Shinohara’s First Style looks to Kiyosi Seike’s houses of the period, for example, the relatively recently demolished house for Professor Saito in Ota Ward of 1952. But whereas Professor Seike referenced Gropius and Breuer, whose US works he would soon be fortunate to see during his travel to America in the mid-50s, Shinohara (seven years his teacher’s junior) was like most Japanese of the period unable to travel abroad. In fact, the financial arrangements for Seike’s apprenticeship to Gropius in Boston proved extremely complex.

Meanwhile, Kazuo Shinohara had been working diligently with students at Tokyo Kodai on domestic field studies, including examinations of folk housing in both town and country (minka) as well as village typologies. These were systematically published by the Japan Institute of Architects as documented field surveys having nothing to do with modernist architecture nor, I think, even with the famous Dialog on Tradition affecting all the arts.

© DEHLI GROLIMUND

For Shinohara at this time visited the then recently restored Jõdo-dõ (1194) erected by Chõgen in the Daibutsu Style at Jõdo-ji in Hyogo prefecture. The connection between that structure and House in White (1966) has been justly remarked, but at Umbrella House with its square shape and pyramidal roof we approach this same form— without the famous Higashiyama cedar pillar that Shinohara requisitioned for House in White.

When I was much younger Professor Shinohara explained to me in the clearest terms that his approach to tradition (which he always referred to aphoristically as a “starting point,” but never a “point of return”) was based on a single feature. This would be usually a structural device allowing for the design of a house whose realization would have been out of the question as a traditional architectural form.

Umbrella House has two salient points in this respect. First is a division between a floored living room-dining-kitchen space and a raised tatami-matted sleeping and dressing space, which occupies the near full dimension of the square-sided plan minus the width of an adjacent vestibule. This affords an oblong stage-like presentation of the raised private space over against the rest, which is intended to be doma -like.

In at least two of his later First Style houses Shinohara addresses this feature somewhat in the manner of Professor Seike’s use of islands of tatami. Namely House with an Earthen Floor (1963) and House of Earth (1966) both originally featured an actual packed-earth doma leading from their entrances as well as the provision of a zashiki or isolated areas of tatami in the manner of Seike.

However, at Umbrella House it is the splendidly exposed rafters that unite these two distinct features of its plan and serve to recall more modestly the exposed structure of the Jõdo-dõ at Ono with its Big Buddha boldness. In order to achieve this column-free span a steel collar (as here shown) had to be inserted to permit the roof’s untraditional span.

© Shozo Kawai

As always, moving (if required) and conservation of any historic building presents a number of problems. Paint colors are a classic example of this and only two original color photos exist for this house. Dismantling the three superimposed layers of white-painted ceiling panel between rafters at last revealed a full color history of rafters and ceiling. Later partially obscured, the rafters as originally installed had been treated with a natural wood stain. However, at some time rafters and framework had received a coat of dark brown paint, which is to be replaced by a natural oil stain.

Umbrella House has of course undergone a number of vicissitudes via repeated renovations, repairs, and extensions. Parts and elements had been lost: the original roofing, all kitchen appointments, wall cloth in the tatami room, the north window of the tatami room, and all bathroom, toilet, and laundry room fixtures, not to mention much of the originally carefully chosen dining and lounge furniture. In fact, most problematic is the roof itself since the original roofing material is today unavailable. Even if it were obtainable, there would soon enough have been issues of waterproofing quite apart from all the differences between current Japanese and German practice. A crucial issue turned out to be the visual sharpness of roof detailing, which even the best modern materials do not necessarily guarantee.

While all this sort of thing is predicable in conservation situations of works since the mid- eighteenth century in whatever country, often a time when “modern” materials and tools began to make their appearance, there were other surprises, such as dry rot induced by oil stove heating in a space where little or no proper ventilation had been provided. Amusingly, according to working drawings the fan rafters ought to have been limited to a mere eight prototypes. In actuality, each rafter was found to have a different proportional section! So much for the much-sung accuracy of Japanese carpentry at least in the helter- skelter of postwar reconstruction. Plus, all measuring and deconstruction had to be done in the heat of the Japanese summer and the midst of a pandemic.

Patience has been the byword at both Vitra and here at Tokyo Tech, as well as for the young local Swiss architectural overseers of this reconstruction project with its international dimension. Professor Shinohara often spoke of the modalities of drawing, construction, and photography as a “fictionality” of the original design as this latter resided in the mind of the architect. A few years ago, House in White also had to be relocated to a new site but of course one within Tokyo. Now for the second time “fictionality” must be understood as applying to preservation and relocation. But all who have been involved as virtual volunteers feel that the translocation of Umbrella House to a European open-air museum would have been viewed by the master as no small personal triumph.

© Damian Poffet

|